Lack of Racial Diversity in Genetic Testing

Although there is a continuous influx of new discoveries in human genomics, there is one aspect where progress is sorely lacking: racial and cultural diversity. The majority of genetic research studies utilize genomic data from individuals of European ancestry. In fact, “70% percent of the data stored in the GWAS catalog is from individuals of European descent, while the other 30% comes from individuals with Asian Ancestry” (Lee et al. 2019). If certain populations are not included in genetic studies, scientists will remain unaware of their fundamental genetic signatures. This can lead to a negative impact in understanding human diseases and development of treatments.

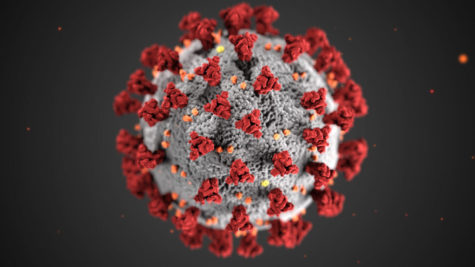

An example of such an impact is the incidence of severe asthma in certain minorities. Doctors have reported for decades that people of African, Puerto Rican, and Mexican descent suffer unusually high rates of asthma-related deaths. (Forno 2012). However, only recently, scientists learned that previously unknown genetic variants are linked to severe asthma. One study identified a novel variant in the PTCHD3 gene associated with severe asthma in African Americans. The study noted that only 5% of previously reported asthma genetic associations identified in European populations replicated in African Americans, underscoring the necessity for including diverse populations in genetic studies to ensure proper treatment is received (White et al. 2016). Another study published in 2018 revealed that African Americans and Latinos have genetic variants associated with a reduced response to albuterol, the main ingredient in most inhalers (Weiler 2018). These variants implicated genes involved in lung capacity, immune response, and albuterol’s diminished effect on these patients. Researchers highlighted a clear association with a variant in the NFKB1 gene, which is more prevalent in people with African ancestry.

Asthma isn’t the only case where traditional genetic knowledge has failed people of non-European ancestry. A study revealed that pharmacogenetic algorithms that predict the correct dosage of warfarin (a blood thinner) for patients over-estimated how much African Americans should be prescribed (Drozda 2015). Researchers found that a certain polymorphism near the CYP2C18 gene is quite common in African Americans and that this variation has tight associations with reduced warfarin clearance from the body. This means that patients carrying this polymorphism should be prescribed a lower dose. Because genotypes highly prevalent in African Americans weren’t accounted for, the algorithms consistently made errors in prediction, resulting in a high risk of hemorrhage (i.e., uncontrolled bleeding), hurting patients rather than helping them.

To tackle the lack of racial diversity in genetic studies, it’s important to look at some of the barriers: distrust due to previous exploitation and lack of finances and infrastructure. Gathering data from diverse populations can be difficult, in part due to the built-up mistrust of research studies from past experiences of exploitation. For instance, the extraction of HeLa cells from an African-American woman, Henrietta Lacks, in 1951 was done without her consent (University of Utah 2021). While these cells fueled the progression of many revolutionary scientific developments, they created an ethical dilemma and reflect the past immoral treatment of minorities. To combat this, local ethics committees now “have a key role in securing compliance with guidelines” and implementing requirements such as the appropriate treatment of study subjects (Sirugo 2019). Ensuring adequate personnel and facilities in certain regions may also be an issue. Even though certain largely untested populations are recognized, collection of data is difficult due to lack of funding. Sufficient investment in infrastructure and professional training is necessary in order to collect reliable data from these regions.

Another important factor to consider is the rising trend in the number of multiracial families in the U.S. due to increased migration. According to the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT), it is projected that by 2050 that the mixed-race population in the U.S. will reach 21%. In order to adapt to the rapidly changing population, thoroughly examining the slightest yet extremely influential genetic variations throughout widespread populations is key to ensuring optimal health for people of all races and ethnicities.

Looking ahead, it is imperative to have greater inclusivity in genetic and genomic studies to improve human health. While just a small fraction of DNA (as tiny as 0.1%) varies between 99.99% of humans, this seemingly minimal difference accounts for major physiological differences we see between people of different racial backgrounds. Increased inclusion of diverse populations facilitates better knowledge of health conditions, development of safe and effective treatments, improved genetic tests, new discoveries in biology and better understanding of human history.

Written By: Aishvarya Godla

Aishvarya is currently a junior at Hinsdale Central. As the founder of the Hinsdale Central Science Journal (HCSJ), she writes and edits articles to publish...