The silence is deafening in room 299 with the exception of the manic and quiet scratches of pencils on paper and many feet nervously tapping on the floor. Along with a few dozen hearts beating out of their chests.

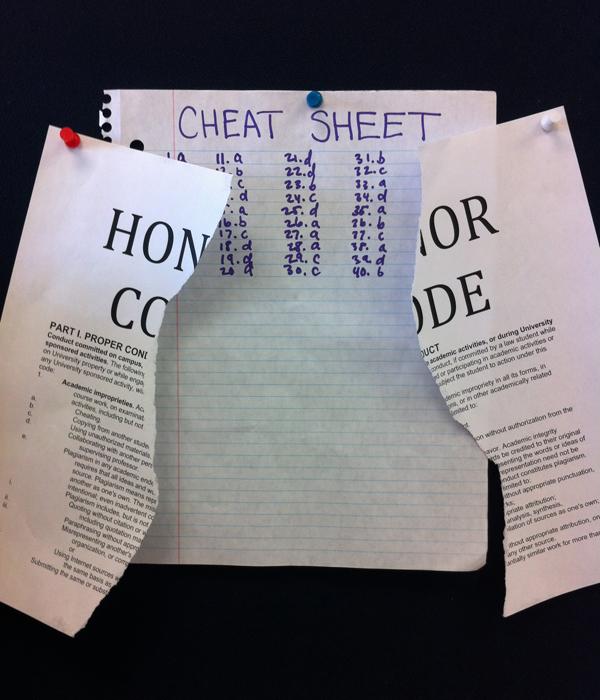

This is the first of Mr. Chris Freiler’s AP European History tests of the year, and everyone wants to do well. While some students silently freak out or lament over not studying enough, others struggle with one of high school’s biggest questions: to cheat or not to cheat?

All of a sudden, Freiler gets up and leaves the room. The students then realize their predicament; they are alone, still taking the test. They shoot alarmed looks across the room at each other, and fidget in the awkward silence. It would be so easy to lean over and ask for the answer to number five.

But not a single stressed-out student does. Every student in the class wants to accept Freiler’s challenge: Can I trust you? And, with only Freiler’s honor code watching, the students continue to take the test in silence. Alone.

Like many teachers at Central, Freiler, a teacher in the social sciences department, trusts his students. He lets that trust coincidewith his classroom honor code to deter students from cheating.

“Hopefully when you’re trusted, you want to be able to earn the trust,” Freiler said. And according to Chetna Mahajan, sophomore, that theory holds true.

“If I was ever tempted to cheat, I would definitely remember that I have signed an honor code and that Mr. Freiler trusts me. So, breaking the trust for me would be what would stop me from cheating,” Mahajan said.

However, it is unreasonable to say that no cheating goes on at Central since it is an unfortunate reality. It seems that the largest issue is educating students about what exactly constitutes cheating.

“To me, cheating is anything that’s submitted for your own work that’s really not your own,” Freiler said. “…Anything that you’re doing behind the scenes suggests that it’s probably not okay.”

The school honor code, established two years ago officially, is more specific as to what exactly breaches academic honesty. The honor code, possibly unbeknownst to many, is printed in every single student handbook on pages 26-28, and lays out what qualifies as cheating and its precise consequences.

According to an excerpt of the honor code, “Copying or communicating assessment material without the express consent of the teacher and/or facilitator…, using unauthorized notes or electronic devices in violation of the guidelines established by the teacher and/or facilitator…,misrepresenting assessed materials as one’s own, submitting falsified information…, stealing or accepting stolen copies of academic material(s).” The honor code also gives more specific examples of these violations and later tells of detailed repercussions such as failing the assignment or course depending on the

severity of the academic dishonesty.

While the handbook does in fact mention that sharing information about a test or quiz is cheating, Chanelle Chua, sophomore, described how frequent it can be to hear talk of assessments in the hallways despite that fact and its effects. Chua doesn’t approve of cheating like most else, but it is hard for her to avoid unintentionally hearing about tests. “I hear rumors about what’s on tests all the time. There’s really no way to stop those,” Chua said.

Mrs. Jennifer Lawrence, Spanish teacher, agrees with Chua. “I believe the most common type of cheating is students telling each other what is on a test they took earlier in the day. I think some students aren’t aware that this is cheating,” Lawrence said.

To prevent the type of cheating that occurs during tests, however, Lawrence asks her students to use dividers to shield them and their tests from possible wandering eyes. Of course, taking this line of prevention is not unheard of within the school.

While Mahajan understands the reason for the dividers, she still is against what the message they subtly send. “Do we really want that in our high school? To be treated like little kids?” Mahajan said.

Freiler is not against covering up tests, but does not use dividers in his class. He does find instances of cheating every once in a while, but says that all hope is not lost for a student who cheats. “It doesn’t mean that it destroys [the trust]. It just means that you have some work to do to mend it,” Freiler said.

While Mahajan seems to agree with the idea that broken trust can be repaired, she does take into account the consequences cheating still has. “I think it’s mostly after you break the trust that you realize that you blew it, and it’s going to be really hard to build that trust back up,” she said.

Lawrence tends to agree with these ideas of rebuilding trust and said that while cheating would definitely change her idea of the individual, it wouldn’t be irreparable. “As a teacher, I tend to give students the benefit of the doubt as far as giving them my trust when I first meet them as students. Over the course of my career, very few students havea lost my trust. I believe if students are aware of the expectations and the expectations are reasonable, then they will abide by them,” she said.

Overall, the general consensus between the two teachers and students seems to be that preparation and awareness of the consequence, a shattered reputation and trust, is key in preventing cheating. “I believe that Central is working diligently to not only prevent cheating, but also to educate students and parents about what constitutes cheating,” Lawrence said. “I try to give them opportunities to practice the format of quizzes and tests. I believe if students feel comfortable about what a test or quiz will be like, the temptation to cheatwill not be an issue.”