Dr. Jim Vetrone’s AP Physics B classes used the scratch-off scantrons on their first test of the year. The new technology lets Vetrone take advantage of the scantron’s benefits, but he also recognizes some downsides.

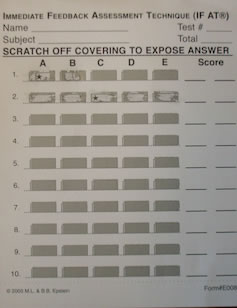

The scratch-scantrons look the same as normal multiple-choice scantrons. However, instead of filling bubbles in with a pencil, students now scratch gray boxes with a coin. A star beneath the gray scratch-off box marks the correct answer. A blank box identifies a wrong answer. Students have three tries to scratch-off the correct answer.

Getting the answer right on the first try rewards a student with three points. Getting it right the second try rewards two points. A correct answer on the third try rewards one point. A fourth or fifth try results in no points.

Senior Will Enright said, “I liked how if I got a question wrong, I could see it right away and try again.”

The scantrons allow students to learn while taking the test because they correct their wrong answers immediately. “They learn as they go along,” Vetrone said.

Senior Samantha Foulston said, “The concept behind them is great because you’re able to see how you did.”

Enright said that the scratch-off scantrons also lowered his overall stress level. “It was stressful in that moment while I was scratching the answer, but then a relief when I saw I got the right answer immediately,” Enright said.

“It’s a hard class, so this builds confidence,” Vetrone said.

Vetrone discloses how the new system can have the opposite effect. “Having the three tries, it can build a false sense of confidence because it’s not like real life,” Vetrone said. This especially comes into play for the AP test—a typical one-chance multiple-choice test. Vetrone recognizes this, so students will use a normal scantron for the class midterm and final exams in preparation.

Written permanency also separates the old and new scantrons. Unlike the AP test and finals (using a pencil and an eraser), scratching off an answer makes it final. “I couldn’t go back and correct my answers. Usually I fill in the answer lightly and go back to change it, but I couldn’t change it with the new scantrons,” Enright said.

Foulston agrees that students struggle to find a way to mark an answer to return to later.

“It takes longer, so I’ve made the tests shorter,” Vetrone said. The first test that students took this year was thirty questions.

For a student like Foulston, who works slower through tests, the scantron was an obstacle for time management while test-taking. “I was halfway or two-thirds of the way done and I was running out of time,” Foulston said. “It would work better for shorter quizzes because it’s a benchmark for how you’re coming along.”

These scantrons cost about five times more than normal scantrons. Vetrone pays for the new ones with extra money from the science budget. However, in order to make this possible for other classes, it would become necessary to charge each student with a lab fee to start the year. Already, chemistry classes charge $20 to cover lab costs.

As it is, only the 40 AP students use these scantrons. “I wouldn’t get them for my regular classes because it’s too expensive to buy them for all the students,” Vetrone said. “I would recommend them to other teachers; it’s just that they’re expensive.”